New Study Finds Over 80% of Key Events in US Latino History Missing From School Textbooks

Jorge Luis Borges used to say that “A book is not an isolated being: it is a relationship. An axis of innumerable relationships.” And the fact is that literature, from fiction to scientific publications, is a testament to human history.

In fact, the passage from prehistory to history began the moment humans began to write about their lives.

Now, imagine these written word compendiums’ power — especially by omission.

According to a new report from the Johns Hopkins Institution for Educational Policy and UnidosUS, much of U.S. Latino history has been omitted from textbooks.

The study found that more than 80% of key events in Latino history are conspicuous by their absence from core textbooks.

“Only 28 of 222 important topics were covered well, leaving out many aspects of the Mexican-American War, the Spanish-American War, the U.S. acquisition of Puerto Rico, the Panama Canal, the modern civil rights movement, Cold War politics, and legal developments shaping the Latino experience, such as the Voting Rights Act, the Civil Rights Act, and racial segregation,” says a release on the report.

Consequently, Latino students in the U.S. are not learning from their history

The Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy and UnidosUS designed a project in the fall of 2022. The idea behind this was to better understand the representation of Latinos in high school U.S. History textbooks.

The study was based on findings that students learn better when they see themselves reflected in curricular materials.

This exploration was critical in a country with nearly 14 million Latino students.

The study explored ten content areas and five textbooks reviewed according to the Johns Hopkins Institute’s Knowledge Map quality measures. The study examined the overall depiction of the Latino experience over the centuries, the balance between discussions of inequality and Latino contributions to the U.S., the use of language, and the authenticity of images, NBC News explained.

There is significant inequality in school textbooks

The study found that topics such as the purchase of U.S. land from Mexico and Latin American politics are studied in depth in history texts. In contrast, coverage of Latino “firsts” in the United States from 1821 to the present was sparse.

This reality is particularly aggravated by political measures in some states, such as Florida, where the banning of some school textbooks appears to rise.

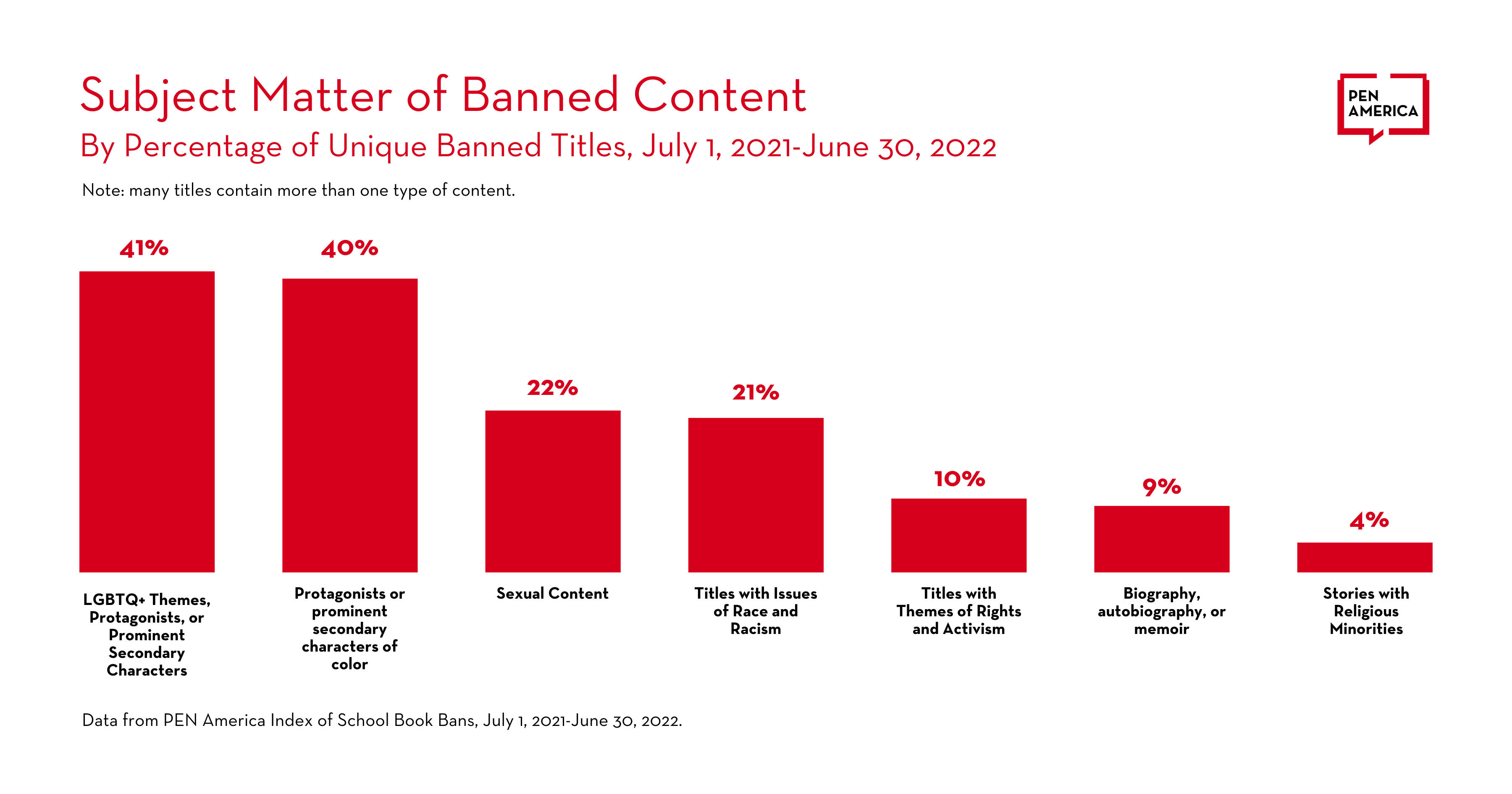

According to the human rights and freedom of expression center PEN America, from July 2021 to June 2022, the Schoolbook Bans Index lists 2,532 individual banned books, affecting 1,648 unique book titles.

The 1,648 titles are by 1,261 different authors, 290 illustrators, and 18 translators, affecting the total literary, scholarly, and creative work of 1,553 individuals.

The bans occurred in 138 school districts in 32 states. These districts represent 5,049 schools with a combined enrollment of nearly 4 million students.

Forty-one percent of the banned books nationwide cover LGBTQ+ issues, while 40% include protagonists or characters of color. Twenty-one percent cover issues of race and racism, while 10% narrate human rights issues and activism.

In its research, PEN America estimates that at least 40% of the bans listed in the Index (1,109 bans) are related to proposed or enacted laws or political pressure exerted by state officials.

What can be done about it?

For the Johns Hopkins Institute for Educational Policy and UnidosUS, solutions are within reach.

While the political situation surrounding the book ban is another matter, the issue of Latino history in educational textbooks is solvable.

The researchers suggest publishers develop textbooks “that fully expose students to the experiences of Latinos, incorporating rigorous content including both primary and secondary sources. At a minimum, publishers should commission independent reviews of their texts, measured against the seminal content.”

Similarly, they suggest that parents and teachers become more involved in determining curricula and materials.

“As the country grows more diverse, it’s essential for our future workers, businesspeople, community leaders, and public officials to learn about the contributions and experiences of all Americans, including Latinos, the country’s largest racial/ethnic minority,” Viviana Lopez Green, senior director of the racial equity initiative at UnidosUS, said in a statement.