Review: Why Huerta’s Namor is a Much-Needed Depiction of Mexican Men Healing Trauma

Since 2018, “Black Panther” has remained both a commercial and critical success acquiring multiple Academy Award wins and one of the largest box offices in history in the process.

Nonetheless, what has set this film apart from other superhero movies is its willingness to address important issues ranging from post-colonialism to the dynamic within a family as they navigate pain. The first installment of the “Black Panther” saga saw an afflicted Erik “Killmonger” Stephens, Jr. lead a coup against King T’Challa as an act of retribution for his father’s death. Marking a clear tone shift from other Marvel films, “Black Panther” explored the themes of father wounds, loss and generational trauma.

Then it would be no surprise that its sequel would revisit these similar issues.

WARNING: This article contains spoilers for “Black Panther 2: Wakanda Forever.”

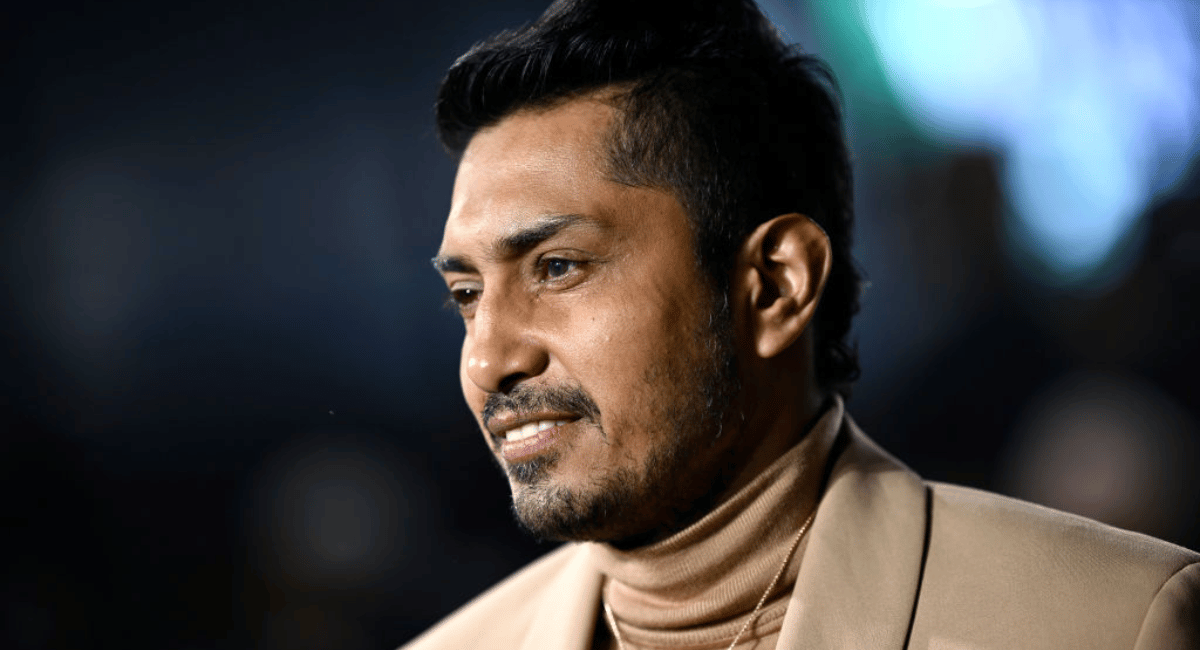

The untimely death of Chadwick Boseman is not absent from the narrative of this sequel. Throughout the movie, Shuri struggles with the pain that T’Challa’s absence has left her, her family and Wakanda. In an emotional scene in which Queen Ramonda urges her to start the process of healing, Tenoch Huerta makes his Marvel cinematic debut as Namor.

It is here where we see the first confrontation between the Wakandans and Talokans and the defining tone that pits Shuri and Namor against each other in the third act.

As the movie continues, Namor is depicted as a warlord who will go to any lengths to defend his fellow people including kidnapping and killing Wakandan royalty. He takes Shuri to Talokan to show her exactly what he is trying to protect. And in an almost unlikely fashion, he opens up to Shuri and bares his heart.

In this particular scene, we see the origins of “Namor.” He is an indigenous boy that comes from a Mesoamerican society who have been ravaged by illness and is only cured by consuming a plant similar to “the heart-shaped herb.” Consequently, this remedy renders his people unable to live on land. As a result, they retreat into the waters of the Yucatán peninsula.

As “Namor” comes of age, he is not ignorant to the poignancy his mother had regarding the life she left behind on the coastline. When the time came to lay his mother to rest, he is considerate of his mother’s sentiments by interring her in the sands of the place she was violently displaced from. Almost immediately, he takes notice of the treatment given to another pueblo originario and attacks their colonialists, getting cursed by a Spanish priest in the process. Upon burning down the Spanish settlement, this priest calls him “El hijo de Satanás. Un niño sin amor.”

It is here where he becomes Namor.

Upon telling Shuri his pain, Namor attempts to recruit her by leaning into her grief. Bringing to mind the conversation he intruded on between herself and Ramonda, he tells her: “You said you wanted to burn the world. Let’s burn it together.” Despite this, she refuses his proposal. Her rejection along with a Talokanan death at the hands of a returning Nakia lays the groundwork for Queen Ramonda’s death at the hands of Namor.

The culmination of the healing journey is in the final battle between Namor and The Black Panther, mantle taken up by Shuri. As they both attempt to strike the lethal blow, Shuri is urged to remember who she was by her mother — now in the ancestral plane. Meanwhile, Namor reminisces on the pain he has had to carry for himself and his people for centuries. At the end, it is Namor who yields and is spared as both sovereigns realize how pain has led them down a destructive path.

In one of the closing scenes, Namora asks her cousin why he kneeled to the Wakandans. His response embodies the tumultuous relationship between the two nations: “The Black Panther had every right to kill me. Why do you think she spared me? She has empathy for the people of Talokan.” Interestingly, as he says these words he is working on a mural canonizing his battle with Shuri further showing to the degree he esteems Wakanda and its new matriarch.

Whether he is sincere in his stance or is just thinking about the security of his empire, Namor is moved by the mercy demonstrated to him. He appreciates the strength by grace afforded him by Shuri and understands the value of a diplomatic tie with Wakanda “as one of the most powerful nations of the surface world.”

“Black Panther: Wakanda Forever” leaves a lot to unpack. But one thing is for sure, whereas the first movie addressed the healing of father wounds, this sequel navigates the healing of those wounds left by the loss of a mother.

Moreover, it depicts the violence of misogynoir through the attack on Wakanda with Queen Ramonda at its helm, as well as her eventual assassination. This is only exacerbated by a man angry at the world, the surface world that took a lot from him and his people. As in its previous installment, Ryan Coogler does an outstanding job in humanizing the antagonist by giving the audience a reason to sympathize with them. But he does not remiss in depicting the consequences of unbridled anger and how it perpetuates cycles of violence along the lines of gender, ethnicity and class.

Above all, “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever” captures the essence of generational trauma and the devastation it brings to families. It cautions us from holding onto the hurt that keeps on hurting. And reminds us the value of healing relationships with ourselves and those around us.