Rafael Ithier Walked So Bad Bunny Could Run. The Salsa Icon Has Died at 99

When Bad Bunny opens “Debí Tirar Más Fotos” with “Nuevayol,” he turns New York into a memory loop. The track samples El Gran Combo de Puerto Rico’s 1975 classic “Un Verano en Nueva York,” a song that already documented Nuyorican life long before Bunny turned it into a global streaming moment. The aux might belong to Benito today, but the blueprint for that sound came from a kid in Río Piedras who played guitar in a corner store for tips.

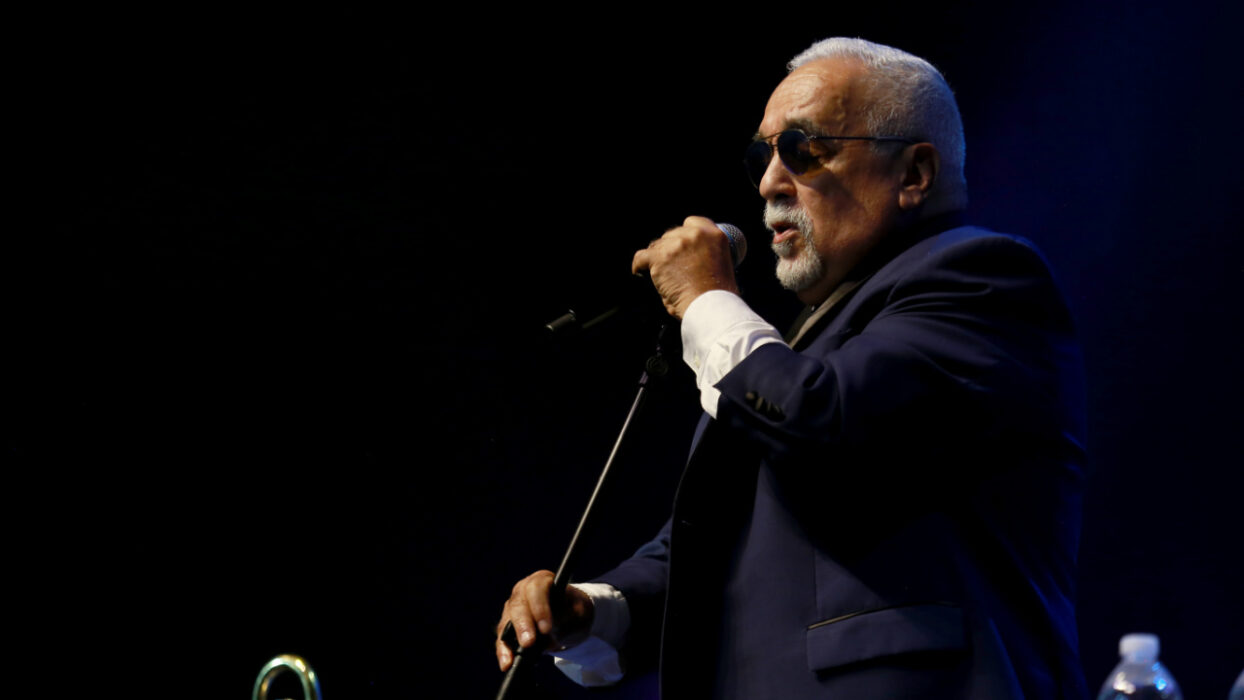

That kid grew into Rafael Ithier. He built an orchestra that people call “la universidad de la salsa.” He led El Gran Combo for more than half a century. And according to Billboard, he died of natural causes on Dec. 6 at age 99, leaving behind one of the most influential catalogs in Latin music history.

Bad Bunny understood that lineage. As news of Ithier’s death broke, he paused his usually quiet social media presence to post a tribute. “Thank you for one of the greatest contributions to Latin music,” he wrote, calling El Gran Combo “part of the soul and culture of people” and declaring that “El Gran Combo is Puerto Rico, and our flag resounds throughout the world. Long live Rafael Ithier!” Billboard reported that he set the post to the group’s timeless “Brujería.”

The message felt less like a generic condolence and more like a confession: his own career stands on Ithier’s shoulders.

How Rafael Ithier lives inside Bad Bunny’s “Nuevayol”

Before TikTok edits and streaming playlists, “Un Verano en Nueva York” already mapped the emotional geography of Puerto Ricans shuttling between the island and the city. NPR described the track as a tribute to the flourishing Nuyorican diaspora in the 1970s, a moment when salsa poured out of New York clubs and studios and back into the Caribbean.

Decades later, Bad Bunny reaches for that exact song when he sets the tone for “Debí Tirar Más Fotos.” “Nuevayol” directly samples “Un Verano en Nueva York” and then mutates into a fusion of reggaeton and dembow, in the same way “Tití Me Preguntó” once twisted old sounds into something new. Bad Bunny told The New York Times that “Nuevayol” was one of the first songs he composed for the album and that it represents the cultural and historical weight of Nuyoricans.

That choice matters. Out of every possible reference point, he went straight to El Gran Combo. Rolling Stone reminded readers that the orchestra’s 1979 album ¡Aquí No Se Sienta Nadie! ranks among the 50 greatest salsa albums of all time. The magazine described El Gran Combo as a “timeless boricua institution” and praised Ithier as an affable leader who focused on groove rather than solos.

So when Gen Z fans loop “Nuevayol” on Spotify, they carry Ithier’s fingerprints in their headphones, even if they do not know it yet.

Rafael Ithier wrote a survival manual in clave

Ithier’s story reads like a manual on how to build a life out of rhythm and stubbornness. He was born in San Juan in 1926 and raised in the working-class community of Río Piedras. His father died when he was eight. By 10, he played guitar at a corner store for tips. At 14, he left school for economic reasons and took whatever jobs he could find, while continuing to teach himself music.

The National Foundation for Popular Culture in Puerto Rico has documented how he moved through a series of local groups. He joined Conjunto Hawaiano as a teenager, learned the Cuban tres and the double bass, and then moved into other ensembles like Conjunto Taoné and Conjunto del Pueblo. Over time, he taught himself to play the piano and to read sheet music.

Then the Korean War interrupted his path.

Ithier served in the United States Army in his twenties. In a 2016 interview with Primera Hora, he admitted, “I have to confess that I cried when I was sworn in as a soldier, because I did not want to be a soldier.” He later said he felt grateful. “I learned the discipline of the Army; I learned to be a man and to obey an order. That discipline is what I apply to my life, and what I base my life on.”

After the war, he moved to New York and formed The Borinqueneers Mambo Kings, named after the 65th Infantry Regiment of Puerto Rico. The band honored a segregated Puerto Rican unit that served in World Wars I and II and the Korean War.

Eventually, he returned to Puerto Rico and joined Cortijo y Su Combo, the orchestra led by percussionist Rafael Cortijo. When singer Ismael Rivera was arrested in 1962, the group fell apart. Ithier thought about leaving music, studying banking, and even law, Rolling Stone reported. Future members of El Gran Combo convinced him to stay.

That decision changed the sound of the hemisphere.

El Gran Combo turned Rafael Ithier into the architect of an era

El Gran Combo de Puerto Rico debuted at the Rock’n Roll Club in Bayamón on May 26, 1962. Ithier sat at the piano. From there, he served as arranger, composer, music producer, and orchestra conductor for more than five decades.

Under his leadership, the band recorded more than 40 albums and played on five continents. The Latin Recording Academy described him as “the architect of a sound that marked generations.”

Billboard’s chart data shows how that sound traveled. The outlet reported that El Gran Combo earned 22 entries on Hot Latin Songs, 41 entries on Tropical Airplay, and 10 entries on Top Latin Albums. The group also holds the record for the most number-one titles on Top Tropical Albums among groups, with 10 chart-toppers.

Those numbers sit behind a set of classics that still soundtrack quinceañeras, cookouts, and heartbreak.

“Un Verano en Nueva York.” “Brujería.” “Ojos Chinos.” “Y No Hago Mas Na’.” “Me Liberé.” When Bad Bunny posted about Ithier, he paired his Instagram Stories with tracks like “Sin Salsa No Hay Paraíso,” “El Caballo Pelotero,” “Nunca Fui” and “Un Verano en Nueva York,” according to Billboard.

Inside the band, Ithier turned discipline into a love language. ABC News quoted singer Charlie Aponte, who wrote that “For me, Rafa was and will continue to be like a father.” Aponte said Ithier “taught us and demanded responsibility, discipline, and professionalism in our work; if you wanted to belong to the group, you had to meet those standards. He made us all better human beings.”

Fans and journalists started calling El Gran Combo “la universidad de la salsa,” the university of salsa. The nickname became the title of a 1983 album and a shorthand for the way young musicians passed through the orchestra, learned, and then carried that knowledge into the wider scene. NPR framed El Gran Combo as an informal training ground for dozens of salsa artists.

That kind of institution-building rarely trends on social media. It quietly shapes every generation that comes after.

Rafael Ithier and the playlist generation

By the time Bad Bunny sampled “Un Verano en Nueva York,” many Gen Z listeners had never held a salsa LP in their hands. They met Ithier’s work through algorithmic playlists, family gatherings, or a TikTok video that used “Me Liberé” as background audio.

Yet the reaction to his death showed how deep his reach still runs. Puerto Rico’s governor, Jenniffer González Colón, wrote that “His music, discipline, and vision, at the helm of ‘Los Mulatos del Sabor’ (or ‘The University of Salsa’), brought the flavor of Puerto Rico to the world.” She added that “His legacy transcends borders and lives on in several generations.”

Local officials echoed that sense of scale.

Ponce mayor Marlese Sifre said, “Puerto Rico has lost a giant, a man whose life was dedicated to elevating our identity through the art and rhythm that distinguishes us to the world,” according to the Associated Press.

For younger fans, those tributes may be the first time they see Ithier named alongside the artists who dominate their feeds. Yet the connection has always been there. When El Gran Combo sang about summers in New York, they documented the same migrant dislocation that Bad Bunny explores when he raps about airports, residencies, and the pull of home. When Ithier insisted on discipline, he built the kind of touring machine and recording standard that makes a song durable enough to be sampled fifty years later.

Streaming numbers can feel ephemeral. Salsa vinyl feels permanent. Ithier lived long enough to see both realities. He watched a new generation of Puerto Rican artists flip his work inside a digital ecosystem he never could have imagined.

Gen Z may know “Nuevayol” better than “Un Verano en Nueva York.” That is fine. Every repeat, every loop on a phone, carries Rafael Ithier’s chord progressions and sense of swing into another decade.

And somewhere between a dusty corner store in Río Piedras and a sold-out stadium in 2025, a straight line connects them.