This Is What Brazilians Think Of President Bolsonaro One Year Into His Presidency

When Jair Bolsonaro was elected as Brazil’s new president people around the world scratched their head in disbelief. He was hailed as “the Brazilian Trump” and newspaper headlines highlighted the return of the far-right in South American politics. Let us remember that previous to the Bolsonaro era Brazil had been governed by the progressive governments of Lula Da Silva and Dilma Roussef, who later were accused and indicted for corruption, accusations that up to this date their fiercest followers deny. So in a climate of political unrest and deep divisions within Brazilian society Jair Bolsonaro was elected.

Just to give you an idea of what Bolsonaro’s politics are, this is a fast and furious summary.

He is: pro-gun, anti-indigenous, misogynist, homophobic, far-right, allied to the most conservative religious groups, anti-press, anti-arts. If you have an ounce of humanity and lead a compassionate life, Bolsonaro is everything that you are not.

So what do people think of him? Tom Phillips, Dom Phillips and Jonathan Watts over at The Guardian interviewed six prominent Brazilians to gather their views on what life is like in the country under the Bolsonaro administration.

Djamila Ribeiro, feminist philosopher, publisher and activist says: “We feel really afraid of the intensifying repression of the black population and the increasing militarisation of the favelas.”

It is no secret that Brazil has very complex racial politics, particularly when it comes to its Black population. Bolsonaro has perpetuated cruel stereotypes about Black Brazilians and racists feel validated (sounds familiar?). Ribeiro is at least a bit positive, though, as she says: “If there’s a positive side to this government, it’s that issues of race and gender have never been talked about so much”.

Patrícia Campos Mello, award-winning journalist, says: “There hadn’t been any kind of censorship since the end of the military dictatorship [in 1985] – and now we’ve started to see a gradual erosion of freedom of expression.”

As has happened in the United States and other Western democracies that have seen the rise of populist politics, the press has been the de facto enemy. Journalists in Brazil feel threatened. To add insult to injury, fake news is now a common denominator in the Brazilian political landscape.

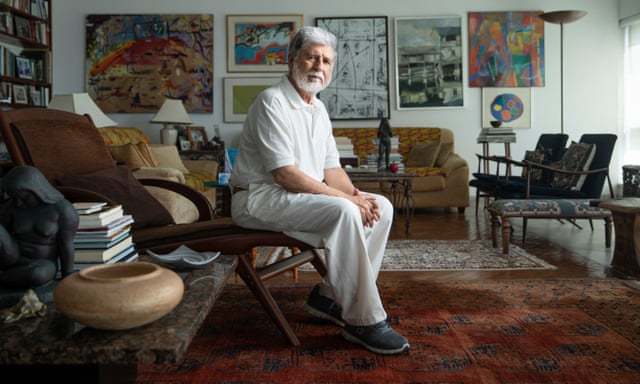

Celso Amorim, former foreign minister, says about Brazilian diplomacy under Bolsonaro: “It’s not very different from the US state department under Trump – only more exaggerated, more ridiculous.”

This veteran diplomat has some very harsh words for the Bolsonaro presidency, and even says he feels ashamed. He adds: “Now it has embarked upon an all-out ideological war against everything that is not western or Christian – according to their conception”. So yes, Bolsonaro’s war escapes the confines of Brazil and determines the country’s relationship to the world. Nice.

Gustavo Bebianno, former Bolsonaro ally, says: “You can agree with him about 99 things. But if you disagree on one and argue or try to offer another point of view, you are seen as a traitor.”

It is often the case that allies and collaborators of politicians who situate themselves in one of the extremes of the political spectrum become disenchanted once the politician is in power. Such is the case of Bebianno, who claims that Bolsonaro is surrounded by radicals and that the administration has become a sort of sect where anything can be judged as treason.

Davi Kopenawa Yanomami, indigenous intellectual, shaman and author, says: “Bolsonaro is a garimpeiro [illegal miner]. He wants more land and fewer Indians.”

Perhaps the population that has suffered the most under Bolsonaro are indigenous Brazilians. Bolsonaro has shown zero respect for their way of life and their relationship with the environment. His timid response to the Amazon fires revealed a pro-industry and neo-colonial perspective in which anything goes in the name of business.

As Davi Kopenawa Yanomami expands: ““In our culture, we don’t damage the river and trees. We care for the forest. But the miners just bring destruction. Who is getting rich from this? It’s not regular Brazilians in the cities. It’s politicians who are selling the wealth of Brazil to foreigners.”

Karine Teles, actor, says: “For Brazilian cinema, 2019 represented a gigantic pause. Nothing advanced. Everything was suspended.”

Regimes that risk becoming totalitarian usually start cutting funding for the arts. Brazilian cinema has been healthy for a few years now, both in terms of revenue and in artistic innovation. However, the Bolsonaro government is attempting to restrict the type of content that is produced with public money, which is a form of censorship.

Teles expands: “I think it’s an attempt to restrict the content of films. But our country is still a democracy where things work in a certain way. No leader – a mayor, a governor, or president – has the right to impose their personal tastes on the entire population.”