Pay-What-You-Can Printing? This Latino-Led LA Studio Is Making Art Accessible Again

Creative geniuses come from all backgrounds—big cities and small towns, wealth and the working class. Yet, “being an artist” often comes with a hefty price tag. If you want to sell or exhibit your art, you must deal with printing costs, which can stack up. That’s where Los Angeles Print Shop comes in, a few blocks south of the city’s Arts District.

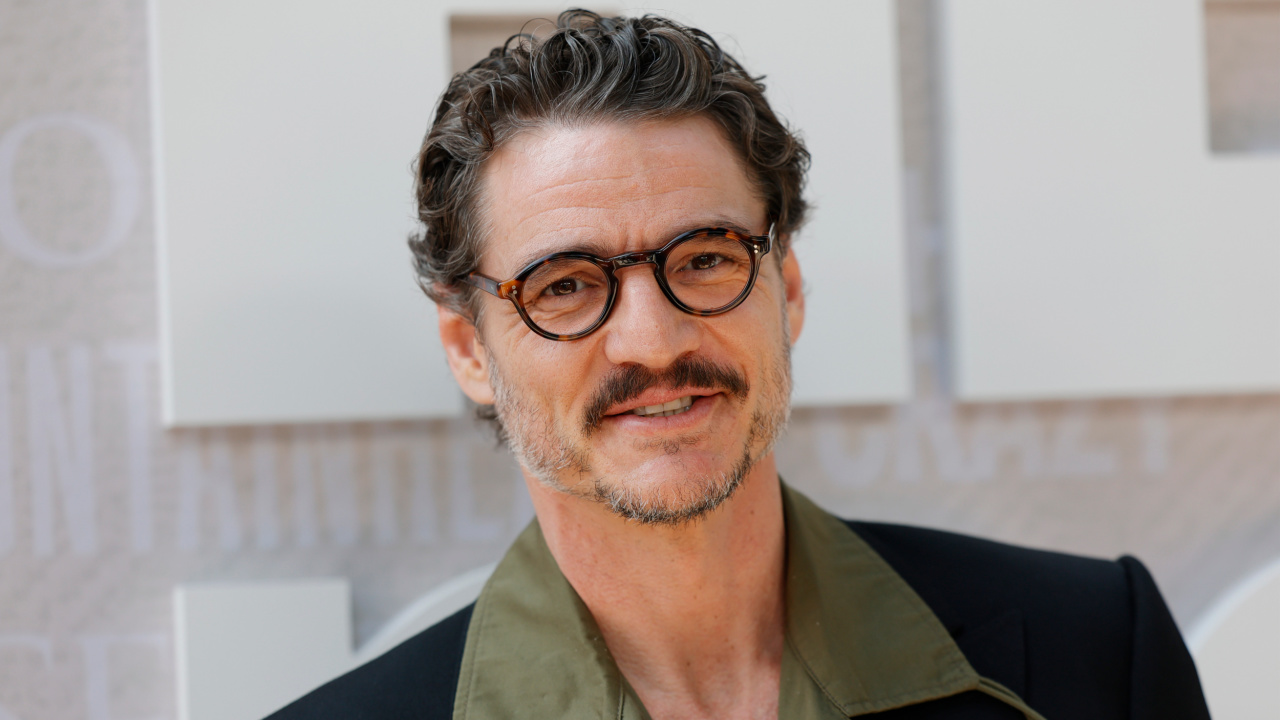

Founded by Esteban Pulido, a Venezuelan-born, LA-based photographer with an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Los Angeles Print Shop aims to make the art world more accessible by offering pay-what-you-can services for all customers. Even if you have nothing to offer—as was the case with some of the print shop’s clients following the Palisades and Eaton Fires—its doors are open for you.

“You can come whenever,” Pulido says. “Whenever you’re ready [or] you have a show down the line, let me know what your budget is, and we’ll make it work.”

Seeing the big picture

The story of Los Angeles Print Shop begins with Pulido’s own backstory as a photographer. Both of his parents were artists, and he quickly learned that he shared their passion: “Art has always been the one thing that can help me better understand myself and better understand others,” he says.

His parents fiercely encouraged him to pursue his artistic aspirations, which he considers a double-edged sword. Growing up, he assumed he would follow a more straightforward path: “Go to school for art, and then you’ll have some sort of art job, and then you’ll sell your work somehow.” “I think that’s possible for some people, but not for most of the people that go to school for art,” he admits. “For me, printing is a great spot to be in because when I went to school for photography, it was a crucial part of my process.”

As an art student, Pulido grew familiar with the printmaking process simply by taking advantage of the resources his school offered. “Whenever the opportunity to be lab monitor or lab assistant came up, I was like, ‘I’m happy to do that.’ And I would do it whenever I could get access to the printer so I could learn how it worked,” he recounts.

Pulido had learned how to use cameras and editing software to make beautiful images, but figuring out how to use a printer opened up completely new possibilities for him.

“Once I learned how to make a print carry qualities like skin tone with detail and exactness, everything changed.”

Armed with this new technical knowledge, Pulido realized that printmaking could be an art, influencing viewers to interact more intimately with photography. “We’re so used to seeing images on our phones, on computers, and on advertisements that we have become accustomed to processing something supremely powerful—one human getting to look at another human—as something regular. It’s almost like watching a cloud pass—there’s nothing to it, in a way. I want to change the way a person experiences that, so they can get back to the feeling of, ‘Oh, shit. This is actually meaningful.”

Pulido elaborates: “If a person just had a haircut, they might have little clips of hair on their skin, or someone might have dirt under their nails or a piece of thread on their shirt.” Bringing out delicate touches like that, Pulido notes, “will slow down the experience a person has when they encounter the photograph and give the photograph an opportunity to be more than just a piece of paper.”

Creating in community

After graduating from art school, Pulido had to seek out his own equipment. Fortunately, he lucked out shortly after relocating to the West Coast. “When I first moved to LA, I didn’t have a printer, but a friend of mine did,” he says.

“I rented a very small studio space and used it to make my own prints. Eventually, they moved out of the country and asked me, ‘Hey, do you want that printer?’ I was like, ‘Yes, absolutely.’ Soon I was making prints for friends, and this organically grew into a business. In the last year and a half, it grew so much that I could no longer do it as a side thing.”

At the print shop, Pulido works closely with business partner Andy Andereg, a writer. “She keeps me grounded—I could spend an entire day making a print. She helps me check back into reality. Most importantly, she and I write the print shop’s newsletter, ‘Making Art at the End of the World,’ together.”

An apprentice, a shop tech, and various volunteers help him move through his queue of prints—although he sees the print shop as a collaborative endeavor rather than a hierarchical one.

“My hope is for the print shop to be a much more horizontal organization. Once it grows to a certain point, it can be something that is not owned by me—it can just be a participatory organization where everyone has a say and a role and a responsibility.”

Running a small business can be tough, even without accounting for programs that give back. Yet making the print shop’s services accessible to all was non-negotiable for Pulido. Thankfully, many of his customers are eager to pay it forward and support other artists in their community.

“I feel super grateful that about half of my customers want to make full-size, full-price prints. They’re doing fine, and they want to be able to help subsidize other artists. On the other hand, there are people who need to make a print but can only pay $50, or $25, or nothing.” Most people, Pulido acknowledges, would see “one of these customers as much more valuable than the other—but here, I can’t do that. That’s not what I want this to be.”

Making art at the end of the world

When historic fires devastated the Pacific Palisades and Altadena neighborhoods, Pulido, like so many other Angelenos, wondered how he could lend a hand. Ultimately, he decided to help in the way he knew best: sharing information about Los Angeles Print Shop’s pay-what-you-can model on Instagram, making it clear that artists who had lost work in the fires were welcome to reprint their art for free.

His post immediately went viral.

“It was overwhelming to see so many people reshare it,” he says. “People I knew, people I didn’t know, people that aren’t even in Los Angeles… There were a couple of big-name actors with followers in the millions who shared it, and tons of people with 200 followers, and people with 10,000 or 30,000 or 200,000 followers. It was this equalizing moment for me: Ok, all of these different people believe that this is something important.”

Of course, Pulido emphasizes, the print shop doesn’t just support artists after large-scale disasters.

Recognizing the tension between art as a personal, intimate practice and art as a potential source of profit is a key aspect of the shop’s mission.

“It was hard before the fires. It was hard before the pandemic. It’s hard to make art, and it’s hard to live, not because we’re not capable, but because the system is set up for us to have to go to work nine to five, unless we come from generational wealth. The system is not set up for us to have non-profitable relationships and experiences. There’s a lot of ‘burn down the system’ going around, which is fantastic—but if we do burn down the system, we have to replace it with actual community.”

Referring back to the name of the print shop’s newsletter, I ask Pulido if he has any advice for “making art at the end of the world.” In response, he shares an anecdote from one of the newsletter’s early issues.

“Andy and I were talking about how challenging it was for us to make art while we were playing with little pebbles outside our door. And the next day, we lined them up in a row, and then we came back again. It’s all about finding a spot in your day to set the pebbles out—and then, if you come back the next day and ask someone else to line them up and look at them, you’ve made art. ‘Making art’ doesn’t have to be going from 0 to 100—finding a model, photographing them, finding the right size for the print, finding a place to exhibit it. If all you can do is take a photograph, or put two pebbles on the ground, you’re starting somewhere.”

In a city where far too many people forget that slow and steady wins the race, it’s inspiring to know that Pulido is helping countless artists lay their pebbles out, one at a time.