Aymara Futurism at 13,000 Feet: How Bolivia’s “Cholet” Architecture Is Rewriting the Skyline

What does decolonization look like in concrete, neon, and glass?

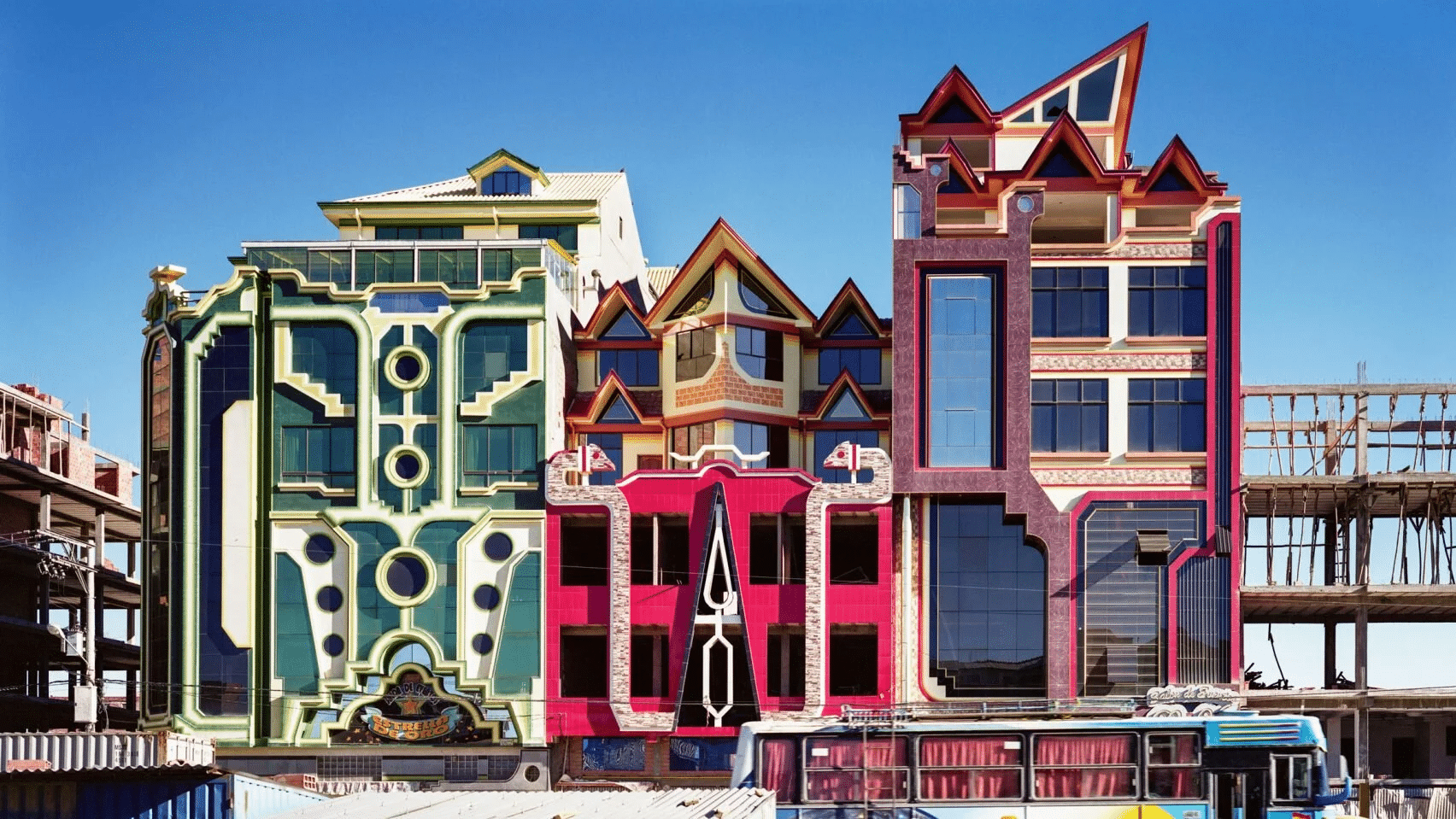

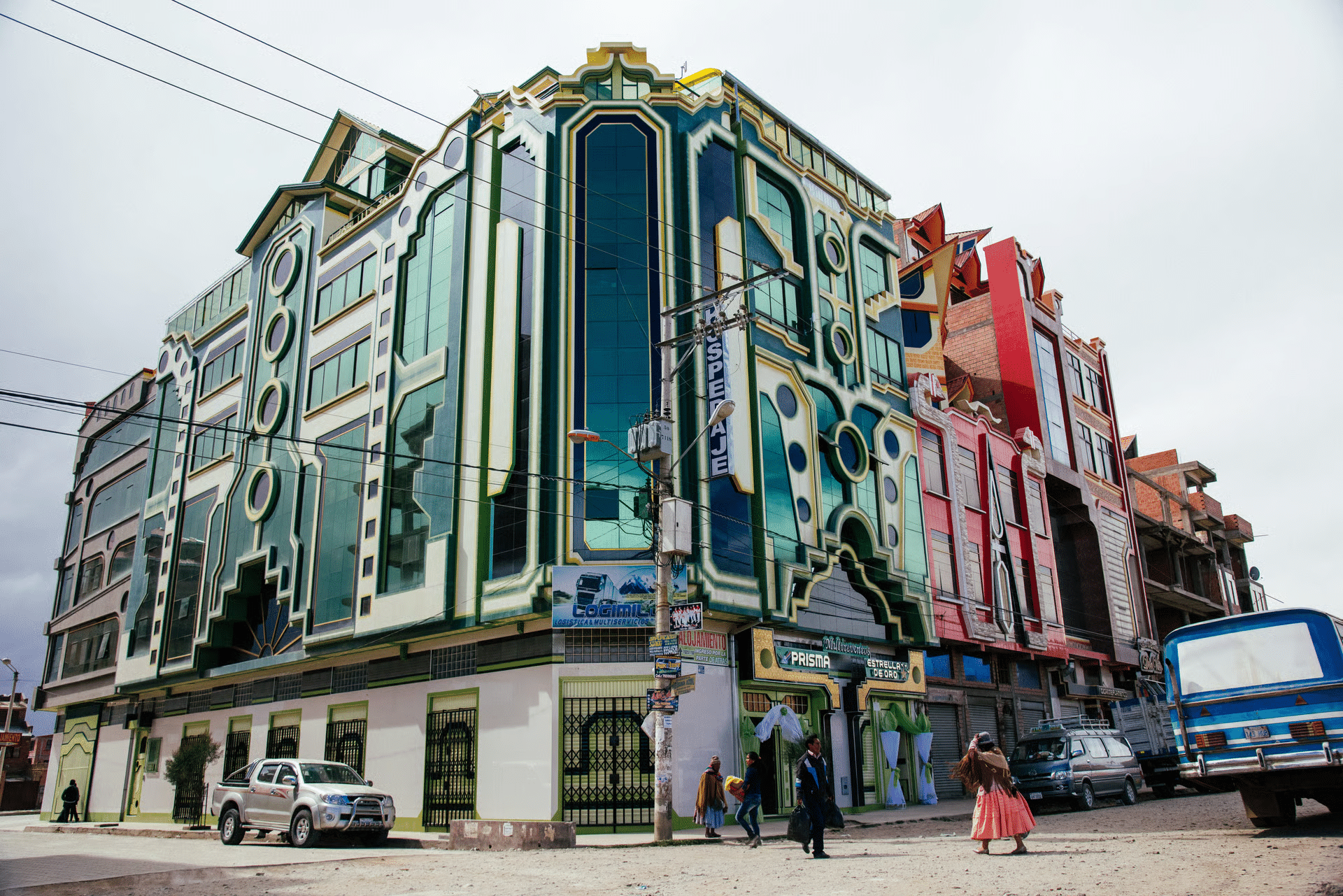

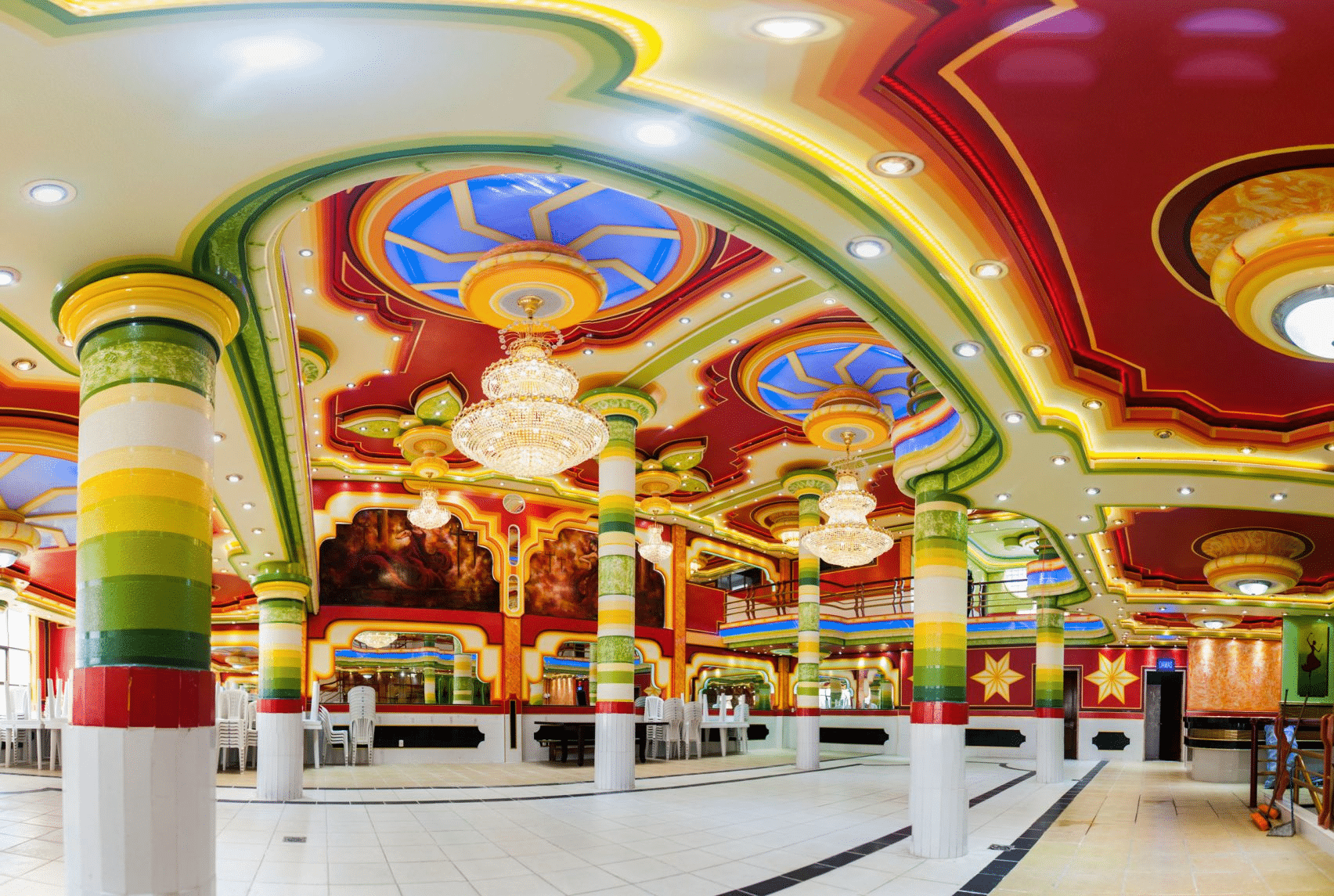

High in the Andes, above the sprawling city of La Paz, Bolivia, a visual revolution is unfolding. In El Alto, buildings now rise and radiate. With candy-colored façades, chandelier-filled ballrooms, and Transformers affixed to rooftops, these structures make a statement that’s louder than any protest. They’re called “cholets,” a portmanteau of “chalet” and “cholo,” and they’ve become symbols of Indigenous power, economic success, and cultural pride.

The rise of the Cholet: From marginalized to monumental

El Alto wasn’t always the Aymara capital of Latin America. Incorporated as its own city in 1987, it started as an informal settlement on the edge of La Paz. Since then, it has grown into Bolivia’s second-largest city and a stronghold of Indigenous political and economic power. Around 80% of El Alto’s population identifies as Aymara, according to a report by the Society of Architectural Historians.

Much of this transformation runs parallel to the emergence of Neo-Andean architecture, largely spearheaded by self-taught architect Freddy Mamani. Since 2005, Mamani has constructed over 100 cholets across El Alto. As Quartz reported, these buildings aren’t subtle. They are vibrant, unapologetic declarations of Aymara visibility, forms of what some scholars now call “Indigenous futurism.”

Why the Cholet became the ultimate status symbol

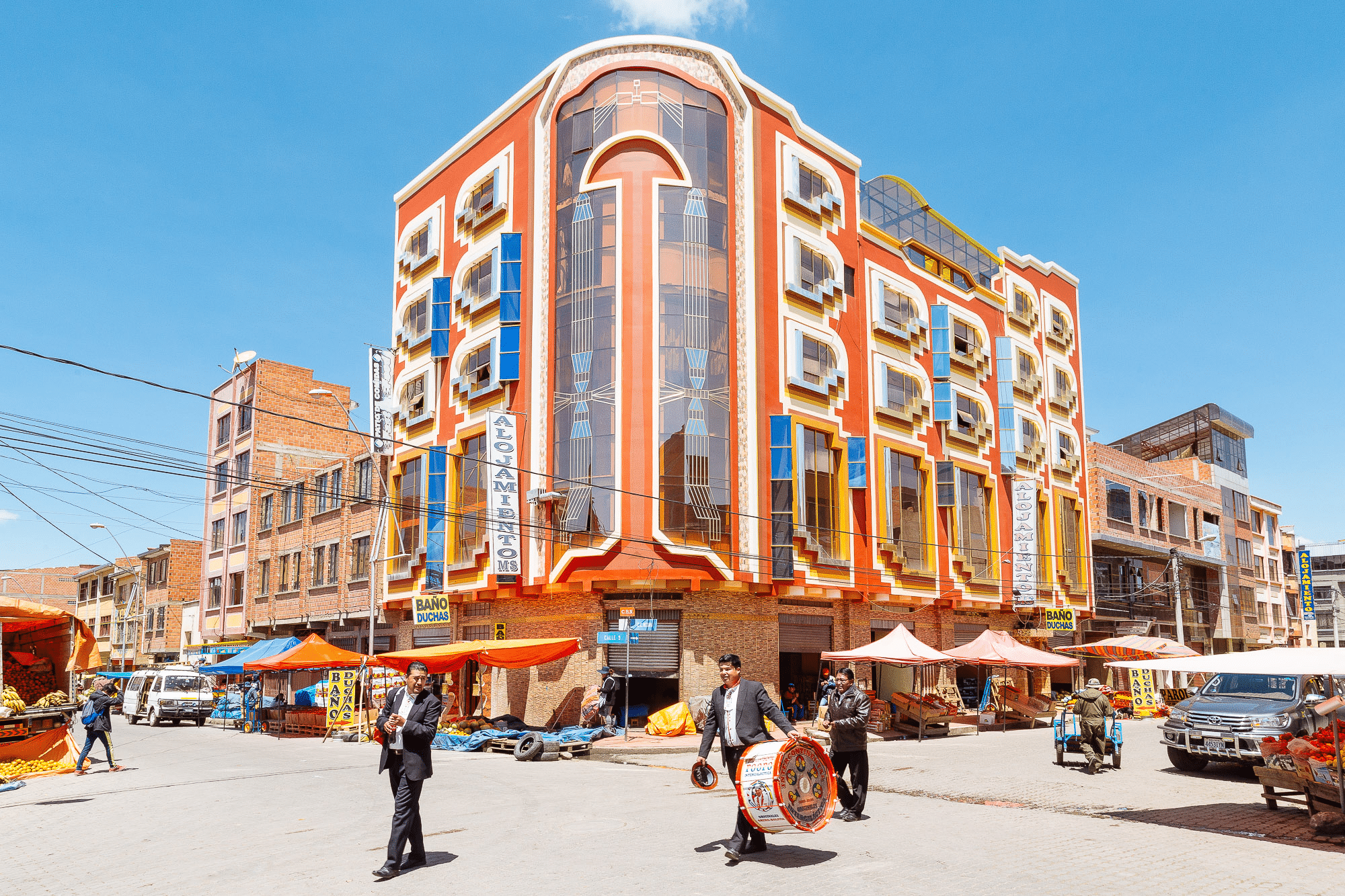

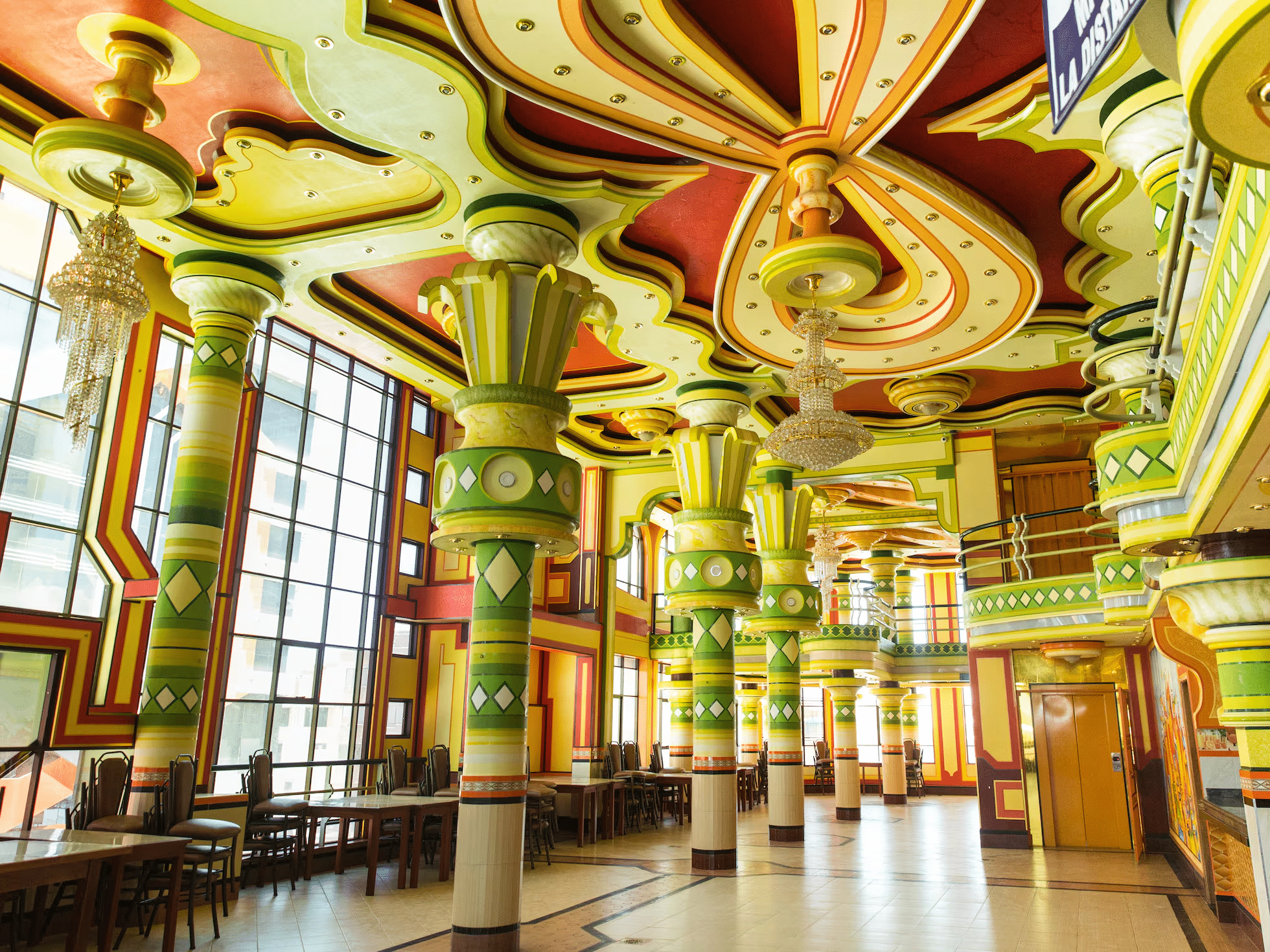

In El Alto, wealth doesn’t hide behind minimalist aesthetics. It dances under crystal chandeliers and bursts from LED-lit façades. According to PIN–UP Magazine, cholets often follow a three-tier structure: commercial storefronts on the ground floor, extravagant party halls in the middle, and private family homes on the upper levels. The opulence isn’t just for show. Renting out these event spaces, often for weddings, quinceañeras, or community parties, can generate enough income to make cholet construction a financially sustainable venture.

According to BBC News, construction costs range between $150,000 and $300,000. While steep, the investment often pays off. One owner, quoted in Quartz, said, “For me, of course it represents the colors of our culture, but mainly it’s the result of hard work.”

Building a Cholet means building community

Constructing a cholet isn’t just about steel and plaster. It’s a spiritual endeavor. As Annie Schentag from the Society of Architectural Historians observed, Aymara builders begin by making an offering to Pachamama, the Andean Mother Earth. These include sugar symbols, candy miniatures, and dried llama fetuses, gifts buried in the foundations to secure the building’s prosperity and safety.

Freddy Mamani himself described the process as more than architectural. “I did it as a cultural, economic, and social assertion through architecture,” he told Quartz. Each cholet is rooted in tradition, yet unmistakably modern.

Stories told in symmetry and color

The geometry of a cholet isn’t random. It’s encoded with meaning. According to Elisabetta Andreoli, a historian of Andean art and architecture, cholet exteriors pull heavily from Tiwanaku iconography, referencing ancient motifs like the Andean cross (chakana) and chacha-warmi symbols of gender duality. Their palettes mimic the traditional aguayo cloths worn by Indigenous women, textiles that themselves once signified village and familial identity.

As Paola Flores reported for the Associated Press, one resident summed it up perfectly: “I am an Aymara woman, proud of my culture, happy and full of color. So why should my home not show what I am?”

Behind every Cholet is a political and economic story

The explosion of cholets coincided with Bolivia’s economic boom and the rise of its first Indigenous president, Evo Morales, in 2006. According to PIN–UP, this period saw the growth of an Aymara bourgeoisie, entrepreneurs who made their fortunes through car imports, Chinese goods, and textiles. These same traders began commissioning cholets as both homes and community centers.

China’s influence runs deep here. The plaster, reflective glass, and LED lights that make cholets shine are mostly imported from Chinese manufacturers. According to Annie Schentag’s fieldwork, some business owners in El Alto even learn Mandarin to navigate these supply chains better.

Transformers and tradition: The aesthetics of abundance

Cholets don’t hold back. Some are inspired by Iron Man, Bumblebee, or even the Statue of Liberty. These motifs are part of what anthropologist Jacques Perkins Martin calls an “architecture of abundance.” In his essay for the Anthropology of Architecture, Martin explains that these buildings integrate global consumer culture as a means of amplifying an Indigenous worldview. The result is a hybrid architecture that is at once kitschy and sacred.

Bolivian sculptor Ramiro Sirpa, who built many of the superhero figures affixed to the buildings, told Bolivia TV that his creations are “one hundred percent Bolivian,” made from metal, fiberglass, and resin.

Cholets are acts of decolonization in brick and glass

In the words of Félix Cárdenas Aguilar, Bolivia’s former vice minister of decolonization, “These buildings are an expression of decolonization, because they’re a way to recover and project our culture.” As reported by Quartz, Cárdenas believes cholets defy centuries of racism that once deemed Indigenous traditions as inferior, folkloric, or illegitimate.

Still, the architecture world hasn’t caught up. Bolivia’s architectural establishment often dismisses Mamani’s buildings as “popular” or “postmodern kitsch.” But to Aymara owners, the flamboyance is the point. As one told researcher Pérez (2017), “The pillars of a building in this design are circular and are stronger and better support the weight of the structure. We are strong, and we work hard, like the pillars.”

A business plan, a cultural hub, and a manifesto

Cholets aren’t just dwellings. They’re active economies. In the Anthropology of Architecture, scholars describe cholets as ecosystems, where each floor performs a distinct function. Some house convenience stores, others operate tech schools or restaurants. They embody a rural logic of densification and multi-purpose space, with every floor and wall designed to generate wealth and visibility.

According to Andreoli, the most opulent party halls can cost up to $600,000 to build but may recoup the investment in just a few years. Some owners like Alexander Chino, profiled by Andreoli, operate multiple cholets, each grander than the last.

What El Alto’s cholets reveal about the future

Bolivia is betting big on its lithium reserves. Chinese-funded infrastructure continues to expand across the country. Meanwhile, El Alto is planning to become a “tecnopolis” by 2030, according to PIN–UP. In this rapidly evolving landscape, cholets represent more than a passing architectural trend. They’re blueprints for a future where indigeneity isn’t pushed to the margins, but centered, where the material becomes spiritual, and where every LED-lit ballroom is a celebration of survival.

When scholar Tassi writes of cholets as “reverberations” of Aymara life, it isn’t a metaphor. It’s the sound of music echoing through party halls, the reflection of light on glass, the pulse of a city that decided it would no longer stay quiet.