Trump’s Green Light for CIA Covert Ops in Venezuela Brings Back a Dark Latin American History

Let’s be clear about the present tense before we rewind. The New York Times reported that the Trump administration “secretly authorized the C.I.A. to conduct covert action in Venezuela,” with a presidential finding that permits lethal operations and coordination with possible military moves.

President Trump then acknowledged the authorization. He told reporters: “We are certainly looking at land now, because we’ve got the sea very well under control.” He also said he approved the move because Venezuela “emptied their prisons into the United States of America” and because of “drugs” coming by sea and, potentially, by land.

However, when pressed on whether the CIA had “the authority to take out Maduro,” Trump replied: “Oh, I don’t want to answer a question like that… But I think Venezuela is feeling the heat.”

The Times also detailed the scale-up: approximately 10,000 U.S. troops in the region, with the majority stationed in Puerto Rico, as well as Marines on amphibious assault ships, eight Navy surface warships, and a submarine in the Caribbean.

The paper reported the U.S. has struck boats off Venezuela, killing 27 people, with the White House claiming the vessels carried narcotics. Similarly, at least five such strikes have occurred since September, and legal experts have questioned the legality of these strikes under U.S. and international law.

Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro responded on national TV: “No to coups d’état carried out by the CIA… Latin America does not want them, does not need them, and rejects them.”

Latin America has seen the CIA in action before

This moment sits on a long continuum. The Times itself wrote that “the C.I.A.’s history of covert action in Latin America and the Caribbean is mixed at best,” then listed episodes that reshaped countries for generations: Guatemala in 1954, Cuba in 1961, the Dominican Republic in 1961, Brazil in 1964, Che Guevara’s fate in Bolivia, Chile in 1973, and the Contra war in 1980s Nicaragua (NYT).

A broad historical overview of U.S. involvement in regime change across the region catalogues the same record and its costs, from coups to transnational repression during the Cold War.

Guatemala 1954 to Cuba 1961: the CIA playbook takes shape

According to the Times, the agency “orchestrated a coup that overthrew President Jacobo Árbenz of Guatemala” in 1954. That operation ended a reformist experiment and ushered in decades of instability and violence. Seven years later, the CIA helped prepare the Bay of Pigs invasion. It failed. There were repeated attempts by agencies against Fidel Castro following that debacle. The historical record shows how those early wins and losses set a template: covert organizing, proxy forces, psychological operations, and efforts to fracture militaries and ruling coalitions.

Brazil 1964 and Chile 1973: how the CIA helped reset power

The Times lists the CIA’s hand in the 1964 coup in Brazil, which toppled President João Goulart and opened a long military regime. In Chile, U.S. agencies financed efforts against Salvador Allende and supported conditions that led to the September 1973 coup. Declassified planning documents cited in historical accounts describe options to “overthrow Allende,” with the Chilean military envisioned as the vehicle for change. The result in both countries: authoritarian rule, systematic repression, and deep social scars.

Operation Condor and the CIA-era regional web

By the mid-1970s, Southern Cone dictatorships built a cross-border apparatus to track, abduct, and kill dissidents. Scholarly and human-rights archives describe Operation Condor as a coordinated system among Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Brazil. Historical summaries note U.S. awareness and support to the region’s security services during the period, even as precise roles varied country to country. The through-line for our purposes: security collaboration across borders magnified the reach and lethality of state violence.

Nicaragua, El Salvador, Grenada, Panama: when Washington pushed harder

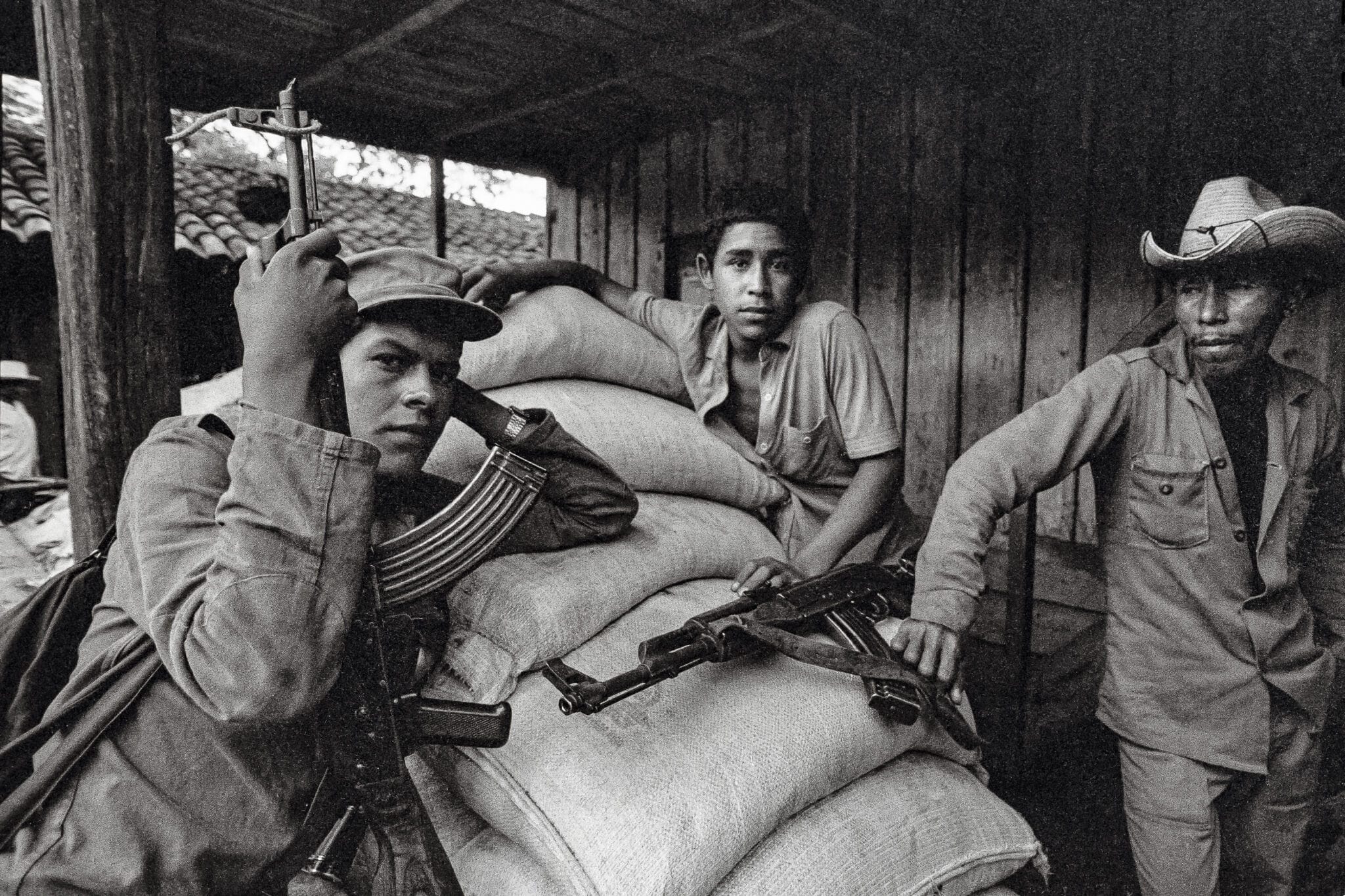

Then there’s the Contra war in 1980s Nicaragua. A broader history also traces how U.S.-trained units in El Salvador committed atrocities during the civil war, including the El Mozote massacre. In 1983, U.S. forces invaded Grenada after an internal conflict on the island. In 1989, the U.S. invaded Panama and removed Manuel Noriega. These episodes sit alongside covert action. Together they underscore a pattern: Washington sought to reorder politics and security in the hemisphere, through clandestine means or by force, and societies paid the price.

Venezuela has lived through U.S. pressure and regime-change talk

The Times calls today’s move a step in a years-long “pressure campaign” to remove Maduro. In fact, Trump said he might order “a land attack.” The White House has already designated Venezuelan groups as foreign terrorist organizations and framed boat strikes as wartime actions.

The Congressional Research Service and multiple analysts have described how the previous U.S. “maximum pressure” push tried to force a political transition, including recognition of an interim government and sweeping sanctions. A consolidated history of U.S. policy notes that those efforts “failed to dislodge Maduro” and deepened the crisis.

So what could come next if history rhymes?

First, secrecy hardens. The Times explains that presidential findings for covert action are among the “rawest uses of executive authority.” Congress gets briefed but cannot disclose details. Oversight stays limited. That has mattered in past Latin American operations. Failures and abuses surfaced years later.

Second, the scope tends to creep. John Ratcliffe, Trump’s CIA director, signaled a more aggressive posture. During his confirmation, he pledged an agency “less averse to risk and more willing to conduct covert action… going places no one else can go and doing things no one else can do,” the Times reported. Past cases demonstrate how initial missions can expand when leaders pursue expedient political outcomes.

Third, regional blowback gathers. Al Jazeera reported that Colombian President Gustavo Petro warned about the potential for spillover if “missiles start falling over there.” History supports the concern. Civil conflicts, refugee flows, and cross-border reprisals followed earlier interventions. Venezuela already sits at the center of one of the world’s largest displacement crises. Any escalation would likely accelerate migration and strain neighbors, as analysts told Al Jazeera.

Fourth, legality becomes a battleground. Al Jazeera quoted legal experts who argued recent maritime strikes likely violated international law and U.S. constitutional requirements. If ground operations follow, those debates will intensify at the U.N., in regional bodies, and in U.S. courts of opinion. Past episodes in the region show how contested legal moves erode legitimacy even when operations succeed tactically.

Finally, costs fall on civilians. That is the through-line from Guatemala’s civil war, to Chile’s prisons, to Central America’s dirty wars. The Times itself wrote that the CIA’s record in the region is “mixed at best.” The history that followed those “mixed” outcomes was brutal for ordinary people.

The bottom line: The present escalation is new in its details. It is not new in its logic. The CIA now has the authority to act in Venezuela, with the Pentagon preparing strike options. Trump’s own words on land operations and Maduro’s response set the stage. Latin America has seen this movie. The opening scenes often look precise, surgical, even righteous. The closing scenes tend to look messy, regional, and human.