The Chilean Government Gave Out Defective Birth Control Pills Which Caused Dozens of Unplanned Pregnancies

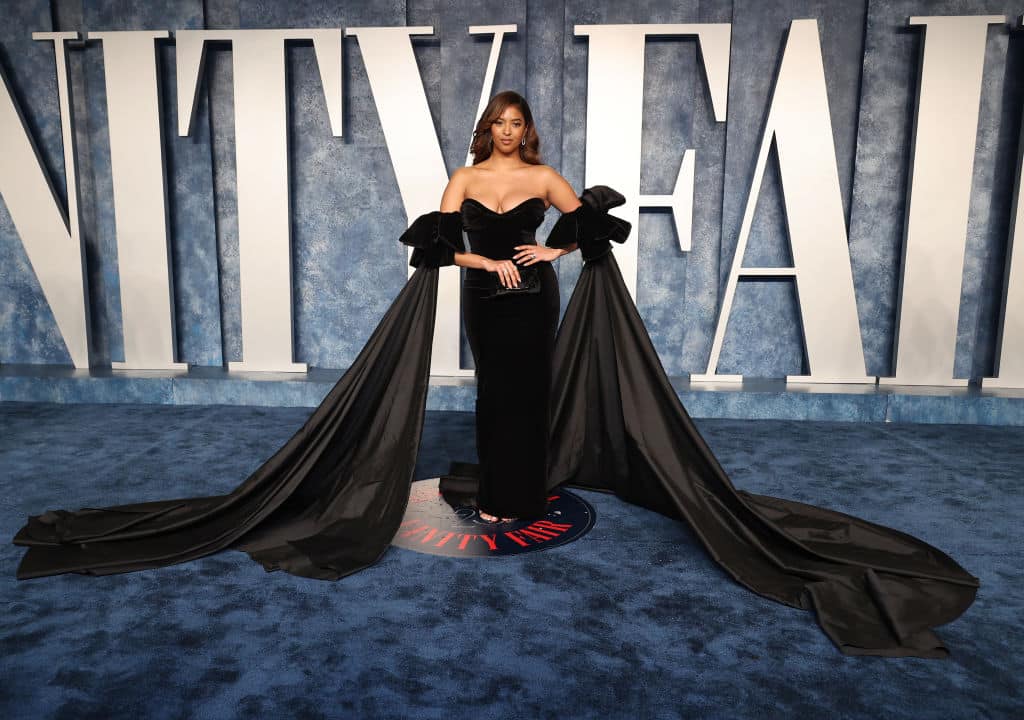

Photo via Getty Images

The fight for women’s right to choose what to do with their bodies is a fight that continues to rage on throughout the world. That fight is especially intense in Latin American countries, where cultural attitudes towards sex and abortion are highly influenced by Roman Catholic ideals.

Recently, women in Chile were provided defective birth control pills from the government. The faulty contraceptives have resulted in at least 140 unplanned pregnancies.

The incident happened when the Chilean government–which is the primary method that women get birth control pills–distributed pill packs that were packaged incorrectly. The pill packs–which went by the name of Anulette CD–had placebo (“sugar pills”) in the place of the active pills.

Reproductive health advocates began hearing rumors that the government had issued defective birth control pills, so they did some investigating. One reproductive rights organization, Corporacion Miles, requested a formal inquiry into the rumors. Because of the inquiry, 276,890 packets of birth control pills were quietly recalled in August of last year.

These unplanned pregnancies are especially challenging because Chile, like many Latin American countries, have very restrictive abortion laws.

someone needs to go to prison for that. saddling people with unwanted children is a crime against humanity.

— 🗣️ citizenswain 🗣️ (she-her-YO!) (@citizenswain) March 2, 2021

Unless a woman has been sexually assaulted or her life is in danger, it is hard to get an abortion in Chile. Because of these laws, women have little means to deal with these unplanned pregnancies. Either that, or they can opt for a clandestine abortion, where their lives could potentially be put at risk.

The Chilean women who became pregnant, after taking every precaution to prevent such a thing from happening, are scared. Many of them, already feeling strained from the emotional and financial strains of the pandemic, don’t feel ready to have a child.

“I don’t think people grasp how hard it is to be a mother for a woman who is not ready,” said Marlisett Guisel Rain Rain, a mother of three who became pregnant with her fourth child after taking the defective birth control pills. “You have to rebuild yourself completely.”

Both the government and the contraceptive manufacturer are pointing fingers at each other for who is to take the blame.

Let women choose. Way too many variables to draft one size fits all laws.

— Brittany (@britknee_00) March 2, 2021

The pill manufacturers are claiming that they have had “no reports” of unplanned pregnancies after taking their pills. But they also insist that if the pills were defective, healthcare workers should have noticed the problem before distributing them. In response, the Chilean government is fining the manufacturer $92,000 due to “quality problems”.

“Women were trusting the pills they were given by state-run clinics,” said said Anita Peña Saavedra, director of Corporacion Miles. “The fault is not only with the laboratory but also with the government. They are both responsible.”

Thankfully, Corporacion Miles is taking legal action on behalf of all of the women who became unwittingly pregnant while taking the defective pills.

"women aged 40 who had interrupted their careers for at least 3 years for maternity or family leave were earning about 30% less than women with no children.

— Loopylafae (@loopylafae) March 2, 2021

The double-duty demands of home and workplace force many women to sacrifice their long-term economic security.

The only bright side that reproductive rights activists see is that this debacle might inspire Chileans to reconsider the countries strict anti-abortion laws come November, when the country will vote on a new government and new constitution.

“This is a very emblematic case to show why having [three legal exceptions] is just not enough and why it is always important to have access to free and legal abortion,” said Paula Avila, a human rights lawyer and head of the U.S.-based Women’s Equality Center.